The Federal Union of European Nationalities (FUEN) is the largest umbrella organisation representing the interests of autochthonous, national, and linguistic minorities in Europe. Founded in 1949, it currently brings together more than 100 member organisations (MOs) from 36 European countries, actively working to defend the rights and promote the cultural, linguistic, and political recognition of minority communities.

FUEN’s mission is not only to preserve the diversity of Europe through the protection of minority identities, but also to uphold international human rights standards and ensure the inclusion of minorities in the political and social fabric of their respective states. In line with this, FUEN has consistently supported the Crimean Tatars by adopting a series of targeted resolutions, calling for justice, legal recognition, and protection from discrimination and repression.

By providing a forum where minority concerns can be elevated to the attention of the Council of Europe, the EU, the UN, and national governments, FUEN reinforces the legitimacy and urgency of these claims. The case of the Crimean Tatars has thus become one of the most prominent examples of FUEN’s active minority advocacy.

Over the past decade, the FUEN Congress has adopted six major resolutions, proposed by the Crimean Tatar member organisation, which has found in FUEN a key international platform for advocating the rights of the Crimean Tatar people. Starting in 2013, and continuing in 2016, 2018, 2019, 2022, and 2024, the resolutions have developed in parallel with the changing political context, from Ukraine’s pre-2014 minority policies to Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and the broader geopolitical crisis caused by the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The core demands across these resolutions include:

* Recognition of the Crimean Tatars as an indigenous people of Crimea.

* Full protection of their cultural, linguistic, and religious rights.

* Immediate cessation of persecution and human rights violations by the occupying Russian authorities.

* Restoration of democratic representation through the Mejlis, which Russia banned in 2016.

* Support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and the reintegration of Crimea under international law.

The resolutions emphasise that the rights of indigenous peoples and national minorities must be upheld according to European and international legal standards. FUEN has repeatedly called on European institutions, the United Nations, and the OSCE to take concrete actions in support of the Crimean Tatars, and has urged its member organisations to cooperate in advocacy efforts.

The Crimean Tatars are an indigenous Turkic-speaking people with a deep-rooted historical presence in the Crimean Peninsula. Their statehood traditions date back to the Crimean Khanate, which existed from the 15th century until annexation by the Russian Empire in 1783. Their modern history has been marked by persecution and forced displacement, particularly under Soviet rule.

In 1944, under Stalin’s regime, almost the entire Crimean Tatar population was deported to Central Asia, accused collectively of collaboration with Nazi Germany. Nearly half of those deported perished due to starvation, disease, and harsh living conditions. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Crimean Tatars began returning to their ancestral homeland. Despite resettling in Crimea, they faced systemic marginalisation, lack of political recognition, and no restitution for confiscated property. Their key representative institutions—the Qurultay (national congress) and the Mejlis—were developed during this period of revival as expressions of collective self-governance.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 drastically worsened their situation. Russia banned the Mejlis, labelling it an “extremist organisation,” in defiance of an International Court of Justice order. Many Crimean Tatars have since been:

* Arbitrarily detained and prosecuted under anti-terrorism laws (especially linked to alleged involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir);

* Subjected to torture, forced psychiatric confinement, and ill-treatment;

* Denied access to education and media in their language;

* Targeted for their religious beliefs (as practising Muslims).

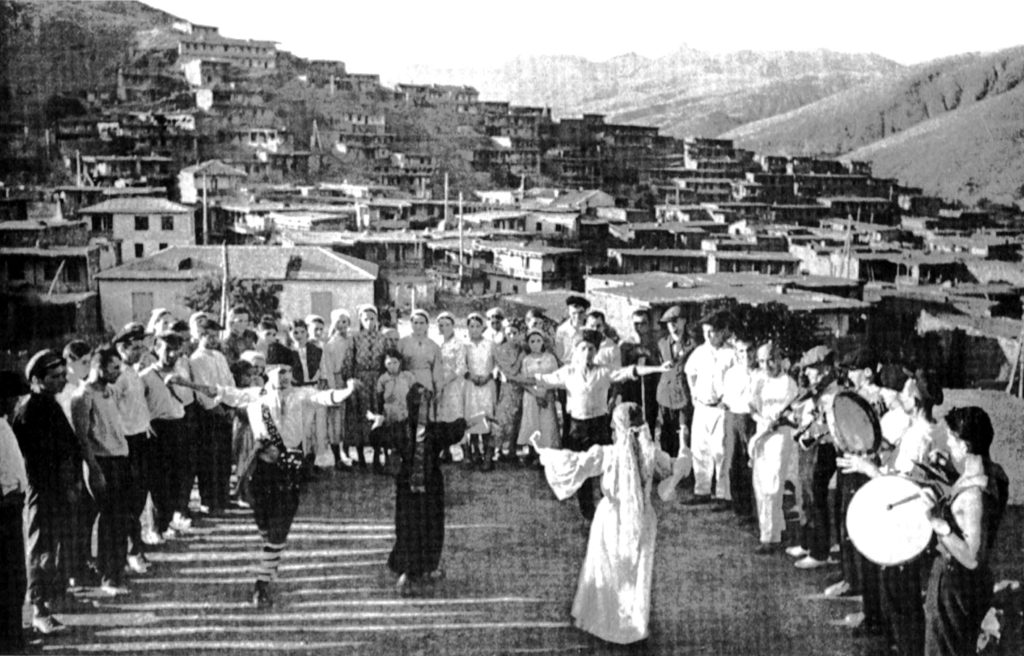

Photo of Crimean Tatars doing traditional dance in the terraced Tat mountains a few days before they were deported on 18 May 1944. Credits to https://www.hurstpublishers.com/soviet-genocide-putins-conquest-crimean-tatars/

While Ukraine has taken positive steps—such as recognising the Crimean Tatars as an indigenous people in 2014 and adopting the Law on Indigenous Peoples in 2021—many of the community’s rights remain unimplemented in practice, particularly in legal and political frameworks. In Ukraine, key legal gaps remain, especially concerning:

* The recognition of the Mejlis in national law;

* The implementation of language and education rights;

* The integration of minority voices in national policy, particularly in post-war reconstruction and EU accession reforms.

The claims made in FUEN resolutions are fully aligned with international minority rights standards, including:

* Ukraine has ratified the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML). These instruments require legal protection, language rights, access to education, and non-discrimination.

* The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) affirms indigenous peoples’ right to self-identification, cultural preservation, and participation in public life through representative institutions.

* The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and ICESCR guarantee freedoms of expression, association, and religion—all routinely violated in occupied Crimea.

International institutions have repeatedly affirmed the legitimacy of the Crimean Tatar cause. The European Parliament, Council of Europe, OSCE, and UN bodies have condemned Russia’s actions in Crimea and supported Ukraine’s efforts to protect minorities. However, their recommendations still need more consistent domestic implementation. What is urgently needed includes:

* Legal codification of the role of the Mejlis and Qurultay;

* Proper funding for cultural and educational institutions;

* Targeted inclusion of Crimean Tatar concerns in Ukraine’s decentralisation and EU harmonisation processes;

* Ongoing international monitoring and pressure on Russia to halt rights violations.

FUEN has not only condemned violations but has consistently provided a roadmap for addressing the challenges faced by the Crimean Tatars. Its resolutions are more than symbolic—they outline concrete steps and identify clear responsibilities:

* Ukraine is expected to finalise the legal recognition of the Mejlis, strengthen its Indigenous Peoples Law, and ensure implementation of Council of Europe recommendations;

* European institutions—especially the EU and Council of Europe—must condition support on measurable progress in minority protection;

* Russia must be held accountable by international courts and institutions for its systemic repression in Crimea.

* Civil society, including NGOs, media, and international watchdogs, must maintain pressure and document abuses;

* Minority solidarity and cooperation are essential: the Crimean Tatars’ case should be supported by other minority organisations within and beyond FUEN. An inclusive, pluralistic alliance is key to building resilience and influence.

FUEN’s message is clear: the continued repression of the Crimean Tatars cannot be normalised or ignored. It is time for European and international institutions to move beyond statements of concern and act decisively to uphold the principles they profess to defend. How many more years must this community endure displacement, discrimination, and silence before justice is delivered?

Amnesty International. (2016–2023). Annual reports on human rights in Crimea. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org

Council of Europe. (1995). Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. https://www.coe.int/en/web/minorities

Council of Europe. (1992). European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. https://www.coe.int/en/web/european-charter-regional-or-minority-languages

Federal Union of European Nationalities. (2013–2024). Resolutions on the Crimean Tatars. FUEN. https://www.fuen.org

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. (2015–2023). Human rights situation in Crimea: Reports and briefings. Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe. https://www.osce.org

Parliament of Ukraine. (2021). Law on Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua

United Nations. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html

United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

European Parliament. (2023). Resolution on the human rights situation in Crimea. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu

Cover photo credits: Crimean Tatar Resource Centre; https://ctrcenter.org/en/the-day-of-the-crimean-tatar-flag-should-have-an-official-status