On 12 December 2022, the Estonian Parliament adopted „The Amendment Law to the Basic School and Gymnasium Law and Other Laws (Transition to Estonian-Language Education) 722 SE”,[1] which establishes that the full transition to Estonian-language education will start in 2024 and would be finalised by 2030.[2] The NGO Russian School of Estonia alerts the international community that this legal act is the ultimate step of the decades-long targeted efforts toward the forced assimilation of the Russian minority in the country. The new law violates the rights to language, culture, and identity of 20% of Estonian citizens (of Russian ethnic origin and/or Russian speakers) and of another ca 5-10% of the population who belong to the Russian minority community but have no Estonian citizenship. Furthermore, it breaches the European Union TEU (Article 3)[3] and the commitments to the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of the National Minorities (FCNM),[4] to which Estonia has been a State-party since 1997.[5]

The right to citizenship of non-Estonian speakers and the use of the Russian language in the public and political life of the state have been hot socio-political issues since 1991 when Estonia regained its independence. Although at the time, the state had explicitly outlined that the Russian language is a mother tongue of a number of citizens of the country,[6] and the first democratic laws outlined the right to Russian language education [7] for the past 30 years Estonia has been continuously limiting the language rights of the Russian speakers. Since the late 1990s, aligning the educational policy with the priority of the Integration Policy to „increase social cohesion through the integration of people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds”,[8] the Estonian government started openly promoting cultural unification (i.e. assimilation of the population with diverse ethnic backgrounds). Targeting the Russian-speaking community exclusively, the decades-long political line of action directly affects and discriminates against about 20% of Estonian citizens. Claiming contribution to the achievement of a cohesive Estonian society, where people enjoy equal opportunities in life, the reforms in the field of education divert from the fundamental EU values of tolerance and respect for diversity and challenge the EU educational priority of multilingualism, based on the principle of “mother tongue plus two”.[9]

* In January 2021, the newly formed government coalition between the Reform and the Center parties signed an agreement, a clause that provided that a transition to a unified Estonian-language education system would be launched. The Ministry of Education formed a working group to elaborate a detailed plan for the complete transition of the envisaged transition.

* In her speech on the Independence Day of Estonia on February 24, 2021, former Estonian President Kersti Kaljulaid addressed the people and demanded the elimination of Russian-language education in the country.[10] As the NGO Human Rights Défense Centre “Kitezh” indicated in their shadow report [11] to the Council of Europe (CoE) on the implementation of the FCNM, this was not the first time when the President had made such a statement.

* On April 23, 2021, the working group, under the leadership of the Ministry of Education and Research, tasked with drawing up an action plan for the transition of the education system to the Estonian language as the only language of instruction, met for the first time.[12]

* In November 2021, the Estonian government adopted the Education Strategy 2021-2035 to guide the developments in the area for the upcoming years. As Estonian media reported, the Action Plan 2035, put forward by the Minister of Education, Ms Liina Kersna, envisages fundamental changes in the current set-up of the multilingual system. According to the Plan, between its inception and 2035, the proportion of Estonian-language education in schools offering instruction in Russian will increase in increments, first to 40%, then to 60 %, and 75%, so that by 2035, all-Estonian education to be in place. As the latest developments suggest, however, the end date of Russian-language education would come even earlier – in 2030.

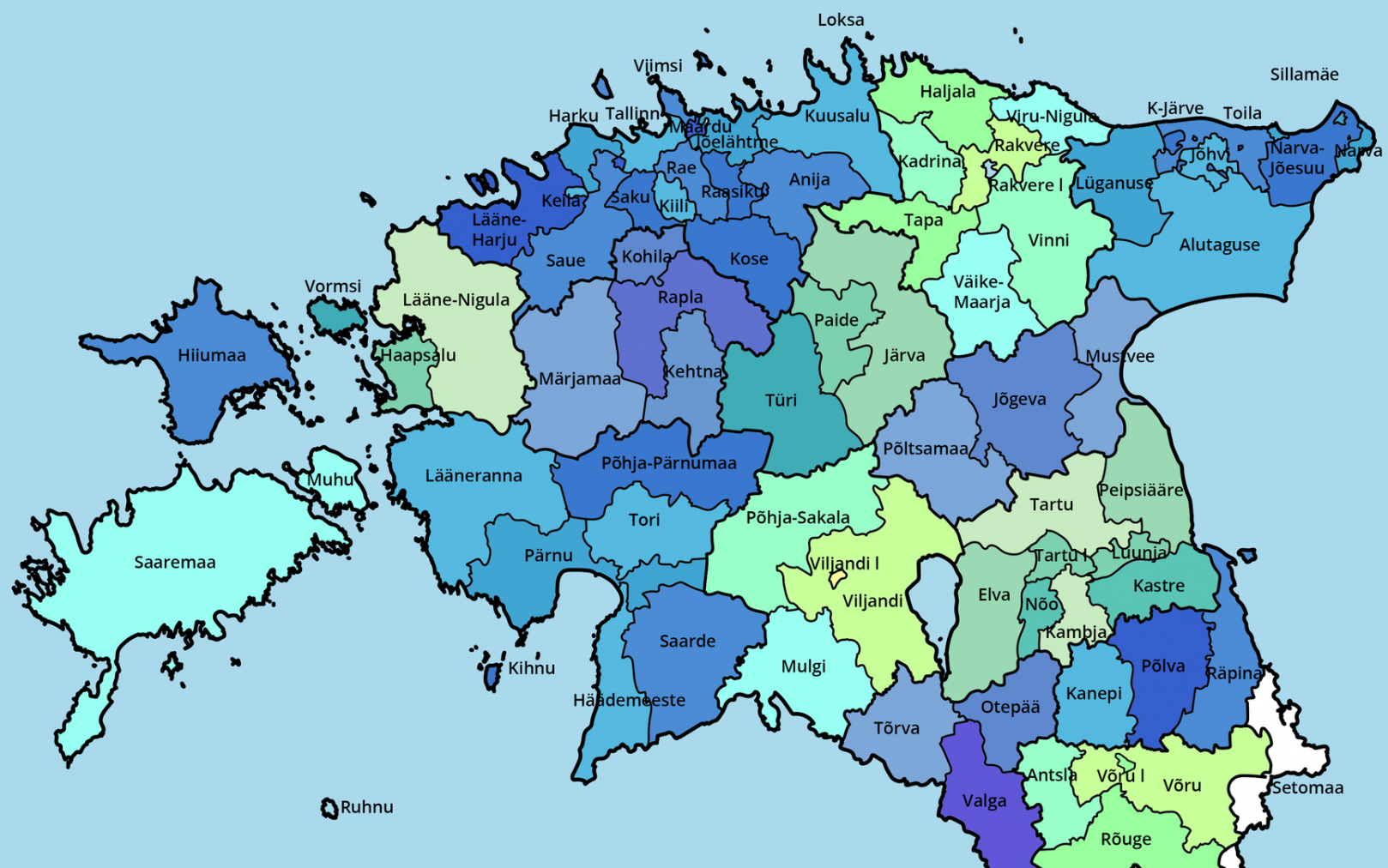

* The Consolidation reform in the field of education in Estonia followed the territorial-administrative reform of 2016-2017 with the aim to optimise the school system in the country but also in line with the "Integrating Estonia 2020" plan.[13] In 2019, 9 small schools (sized between 100 and 530 pupils each) were consolidated, and the children were provided with the option to choose between learning only in Estonian or bilingually under the model 60% Estonian to 40% Russian. The Consolidation, therefore, has led to two curricula running in parallel – the so-called “2 in 1” schools.[14] The "Integrating Estonia 2020" plan also envisaged that the Russian-only gymnasiums in Estonia introduce the bilingual model of 60/40 Estonian to the Russian language. In some rural areas, however (with Russian ethnics as a majority), the 60/40 model required by law could not be applied due to the lack of specialists to teach in Estonian (such, for example, in the tiny town of Mustvee, wherein the local school there are just 42 students in grades 10 to 12).

* According to Estonian law, the language of instruction in upper secondary schools is Estonian. Still, the law provides that the language of instruction may be another in municipal upper secondary schools or single classes thereof. The Government of the Republic can grant such permission or approve a bilingual model of studies on the basis of an application submitted by a rural municipality or city government.[15] The fact, however, that the Estonian Government provided an exception to the 60 % rule for the Tallinn German Upper Secondary School but refused to make a similar exception for several schools delivering instruction in the Russian language can be seen as an act of discrimination based on ethnicity.[16]

* Throughout 2021, in line with the Consolidation reform, a number of schools in Russian-speaking villages and cities delivering education in Russian language or bilingual Estonian-Russian education were closed. Students were automatically transferred to local Estonian-only schools with the promise that there would be provided with an opportunity for classes in the Russian language until their graduation. In many cases, such a possibility was not offered. However, for first-grade children from Russian-speaking communities, such an option was not envisaged, and they were enrolled in Estonian-only classes. As the NGO Russian Schools reports, a number of families, therefore, decided to move from Keila to Tallinn, where schools are still offering Russian language or bilingual education.

* According to the representatives of the Russian-speaking community of Estonia, the reform in the education field is aimed not only at optimising the school system but at the gradual eradication of Russian education in Estonia, which would eventually lead to the assimilation of the minority. The local communities see the closing of small schools in Russian-speaking areas as a social catastrophe since, in many cases (such as in the cases of Ämari, Keila, and Kallaste), the closing has affected negatively not only the access to education (due to the fact that schools offering Russian-language options are located at a significant distance from students’ home-villages) but also to internal migration of whole families to bigger cities (where they can sign-up their children in Russian-language or bilingual schools). Furthermore, particularly concerning for the minority is that it is not only small schools that have been “optimised” but also that schools with more than 200 students, such as the one in Kiviõli, might have the same fortune. Although the Russian-language school in Kiviõli is still functioning, the community is worried about the fact that at the level of the local government, there have already been discussions about its future optimisation with no consultations conducted with the concerned population.

Considering languages as an expression of one’s culture,[17] as early as with the Treaty on European Union (TEU),[18] the EU has required that the Member States respect linguistic diversity (Article 3, TEU) also when developing the European dimension in education (Article 165(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)[19]). In 2000, the legally binding Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union[20] prohibiting discrimination on grounds of language affirmed the respect for linguistic diversity as an obligation (Article 21). In pursuit of the policy line, in 2002, the European Union Council meeting in Barcelona adopted the educational principle “mother tongue plus two [languages]”,[21] acknowledging multilingualism as a mechanism that increases the mutual understanding between different cultures,[22] economic progress, and social cohesion.[23] However, the EU has made explicit that by promoting and developing this key competence through their educational policies,[24] the Member States shall ensure that learners do not lose touch with their language of origin.[25]

By placing a focus on learning a minimum of two foreign languages at school alongside the mastering of the mother tongue,[26] by acknowledging the role of diversity in all of its Integration plans, and by aiming at enhancing equality and social cohesion, the Estonian state nominally adheres to the EU policy lines. Nevertheless, the Estonian laws appear to align with the EU requirements and with the international standards for the protection of the cultural rights of the national and ethnic minorities in Europe only nominally. The general state policy and long-term developments (over the decades) have placed the language and educational rights of the Russian minority under constant attack. The recent decisions of the Parliament are not only breaching the state's Constitution but also abolishing international commitments (FCNM) and European regulations, policies, and fundamental values.

The practice reveals a trend of systematic and targeted implementation of measures which do not contribute to social cohesion but facilitate the assimilation of Russian-speaking Estonian citizens, many of whom identify as belonging to a national minority community. The reforms in the field of education, the closure of Russian-medium schools, and the plans to shift to all-Estonian education are seen not only as a violation of the cultural and minority rights protected by the FCNM but also as mechanisms that target the eradication of the Russian-ethnic-consciousness of the young minority representatives through both incentives or forced measures. The fact that the Estonian government has been granting unequally the exception from the 60/40 rule to schools (e.g. such was provided to the Tallinn German Upper Secondary School but rejected to several Russian language schools) has also been fuelling tensions among the Russian ethnics and increasing their feeling for being discriminated against. The lack of efficient policy measures to expand bilingual education opportunities and increase opportunities for contact between the majority and the minority communities[27] continue deepening the divides between Estonian and Russian language schools and contributing to segregation. Regardless that since 2013 Estonia has started developing a two-way immersion program (allowing children from Estonian and Russian backgrounds to study together and master their mother tongue while learning the other language), until 2020, its implementation was limited only to several kindergartens in the country.[28]

The concerns of the Russian minority do not stem only from the flexible interpretation of the legal provisions regulating the field of education and their selective implementation but also from the constant political push to adopt an Estonian identity based on the Estonian language and culture. In this context, the school system's reform is not seen as positive and potentially bringing in the expected higher quality of education and equal opportunities in the labour market and life in general but as a mechanism to open the doors to gradual assimilation. Limiting the rights of Russian-speaking Estonians to pursue education in their mother tongue appears to be a direct threat to the possibility that they preserve and maintain their cultural identity. The new policy strategic plans for eradicating the Russian-medium schools enhance the fears among the minority members.

Considering that by reducing the educational opportunities in the Russian language, the state is challenging not only the rights to language, culture, and identity of a national minority but also of EU citizens from diverse cultural backgrounds, the international community needs to take a stand against the adopted approach by the Estonian government to societal cohesion, which contradicts the human and minority rights standards. A cohesive Estonian society can be achieved only if all stakeholders put efforts together to find common ground for mutual understanding and to live together. Imposed integration, disregarding diversity, is nothing less than assimilation. Hence, the democratic way forward is that the Estonian government involves Russian speakers in the public debates on the issue and the decision-making process.

Between 2018 and 2022, four FUEN Resolutions[29] adopted by the Assembly of Delegates of the Member Organisations focused on the challenges faced by the Russian minority in Estonia. The violation of the educational and language rights is also a violation of the right to identity and culture, and hence - a breach of the provisions of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, to which the Estonian state is a party.

FUEN, therefore, calls on the Government of Estonia:

* to comply with all articles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and adhere to the recommendations of international organizations (OSCE, ECRI, etc.)

* to reconsider the policy of violating the educational and language rights of the Russian-speaking Estonian citizens and to end the policy of closing Russian-language schools without ensuring that the population is provided with identical educational opportunities in the cases of implemented reforms/optimisation of the school system.

* to adhere to the key European value of multilingual education and to revise the Program for the development of the Estonian language 2021-2030, which aims at a full transition to Estonian-only education.

FUEN calls on the EU, CoE, and the European Institutions at large:

* to take a firm position against the policy of Estonia in relation to the Russian national minority and the attempts to enact forced assimilation, which contradicts the TEU (Art.3), the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Art. 5, 14, 16 and others), the Hague Recommendations of the OSCE. Violating the rights to language, culture, and identity of European citizens of diverse cultural backgrounds, the Estonian government acts against the fundamental values and principles of the EU.

* to require that the Estonian government respects and adheres to the European values of diversity and multilingualism in the field of education and to comply with the international standards and obligations resulting from ratified legal instruments of the CoE, OSCE, UN, and the EU.

A detailed report on the case of Russian-language education in Estonia will soon be available on the FUEN website [a link is to be placed here]

[1] The Ammendment Law to the Basic School and Gymnasium Law and Other Laws (Transition to Estonian-Language Education) 722 SE https://www.riigikogu.ee/tegevus/eelnoud/eelnou/1e58a907-7cd0-41b9-b898-aa8eee5e94bf/P%C3%B5hikooli-+ja+g%C3%BCmnaasiumiseaduse+ning+teiste+seaduste+muutmise+seadus+%28eestikeelsele+%C3%B5ppele+%C3%BCleminek%29

[2] Ministry of Education (in English), „Transition to Estonian-language education”, https://www.hm.ee/en/node/234 and „Minister Tõnis Lukas: Transition to Estonian-language education will definitely happen”, https://www.hm.ee/en/news/minister-tonis-lukas-transition-estonian-language-education-will-definitely-happen

[3] Treaty on European Union, Consolidated version 2012, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:12012M/TXT

[4] Estonia signed the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of the National Minorities (FCNM 1995, https://rm.coe.int/16800c10cf) in 1996. It entered into force as of 1998

[5] Council of Europe, State parties to the FCNM, https://www.coe.int/en/web/minorities/etats-partie

[6] The Development of Education, National Report of Estonia by the Ministry of Education (August 2001), submitted to the International Bureau of Education, UNESCO http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/International/ICE/natrap/Estonia.pdf

[7] Republic of Estonia Education Act (Rt 1992, 12, 192), Article 2, https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/524042014002/consolide/current

[8] https://kul.ee/media/438/download

[9] Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on key competences for lifelong learning, 18.12.2016 (2006/962/EC)

[10] https://president.ee/ru/official-duties/speeches/14994-24-2019/index.html

[11] NGO Human Rights Defense Centre “Kitezh”(September 2021) Alternative Report for the Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

[12] https://rus.err.ee/1608190003/sostojalas-pervaja-vstrecha-rabochej-gruppy-po-perehodu-sistemy-obrazovanija-na-jestonskij-jazyk

[13] Report on the implementation of the implementation plan of the development plan "Integrating Estonia 2020", 2019, pp 24-30, https://kul.ee/media/425/download

[14] The Estonian Experiment: How Tallinn Deals with its Russian Schools, REBALTICA.LV, 2019: https://en.rebaltica.lv/2019/02/the-estonian-experiment-how-tallinn-deals-with-its-russian-schools/

[15] Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act (RT I 2010, 41, 240), Article 21(2) https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/525062014005/consolide?current

[16] Estonian Court Confirmed the Ban on Teaching in the Russian Language in Russian Schools, NEWSRU.COM, Aug. 26, 2016

[17] Fact Sheets on the European Union: Language Policy, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/142/language-policy

[18] Treaty on European Union, Consolidated version 2012, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:12012M/TXT

[19] Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Consolidated version 2012, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:12012E/TXT

[20] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf

[21] Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on key competences for lifelong learning, 18.12.2016 (2006/962/EC)

[22] European Union, Education Policy, https://ec.europa.eu/education/policy/multilingualism_en

[23] EC (2017), Education and Training Monitor 2016, Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union: p. 29

[24] European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Day, L., Meierkord, A., Rethinking language education and linguistic diversity in schools: thematic report from a programme of expert workshops and peer learning activities (2016-17), Publications Office, 2018, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/584023, p.2

[25] EC (2008), Multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment, COM(2008)566 final

[26] Ministry of Education and Research of Estonia, Foreign language learning in Estonia, https://www.hm.ee/en/activities/estonian-and-foreign-languages/foreign-language-learning-estonia#:~:text=In%20Estonia%2C%20students%20traditionally%20learn,as%20their%20first%20foreign%20language

[27] 5th Report Submitted by Estonia to the Framework Convention, ACFC/SR/V(2019)014 17, https://vm.ee/sites/default/files/5th_sr_estonia_en.pdf

[28] Eurydice, National Country Reports: Estonia, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/national-reforms-school-education-20_en

[29] FUEN Resolutions 2022-05, https://fuen.org/assets/upload/editor/docs/doc_m8FnA9r5_Resolutions_2022_EN_Q.pdf

FUEN Resolution 2021-04 (Urgent Resolution), https://fuen.org/assets/upload/editor/docs/doc_lgSIDMCb_Resolutions_2021_EN.pdf

FUEN Resolution 2019-03, https://fuen.org/assets/upload/editor/docs/doc_kh9bLA0l_FUEN_Resolutions_2019_EN.pdf

FUEN Resolution 2018-02, https://fuen.org/assets/upload/editor/FUEN_Resolutions_2018.pdf